Last week in response to marginally better than expected labour market data for the December quarter the financial markets shifted from pricing in the next cash rate move as a cut to pricing in a rise by the end of May. One forecasting group shifted their call to predicting two more rate rises.

First, why predict more rises? It pays to realise that if you’re an economist working in a dealing room the thing you need to sell is not a record of rate forecasting success – no-one has that – but of convincing rate change views. Your dealers and client advisers need something to go to their clients with even if it is only an explanation of divergence from the views of others.

Divergence is good but a calculated gamble as deviating from the pack can risk reputational damage if you are wrong. That contact opportunity can lead to trading business which is the reason for the existence of many people in the room.

Less cynically, the Reserve Bank last November predicated its view of no more rate rises on data falling in line with their expectations outlined in the forecasts section of their Monetary Policy Statement. However, the stronger than expected data means the risk of wages growth slowing as they hope has been diminished.

The problem for the rate rise pundits however is that some of the RB’s forecasts have also proved too high and the outcomes imply less inflation than they have pencilled in.

For instance, they estimated that the NZ economy grew by 0.3% in the September quarter. In fact it shrank 0.3%. They also estimated that the CPI rose by 0.8% in the December quarter. In fact it rose by 0.5%.

These data divergences are one reason why not everyone is jumping on the excited rate rise wagon and why the risk is that the markets have pushed swap rates unsustainably high at the moment.

It also pays to note that the Reserve Bank have emphasised that it is core inflation measures which they focus on and as one other forecasting group pointed out this week, some are falling faster than they shot up.

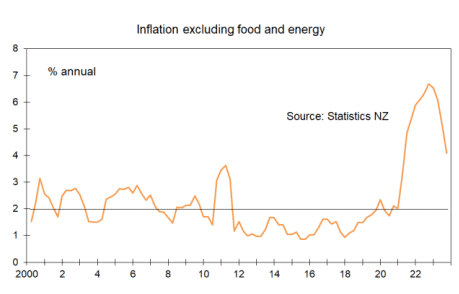

Consider for instance one of the measures which attracts a lot of attention in the United States – the CPI excluding food and energy. Four quarters before the peak in this rate of 6.7% in the December quarter of 2022 the rate was 5.4%. Now, four quarters after that 2022 peak rate of core inflation the change is 4.1%.

The measure of inflation excluding the top 10% of risers and fallers however peaked at 7% in the September quarter of 2022 and five quarters before then was 3.2% whereas now five quarters after the rate is 5.0%.

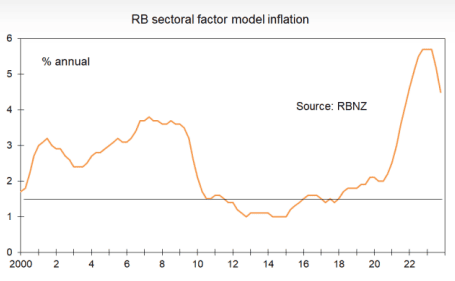

The sectoral factor model inflation measure calculated by the Reserve Bank and published in their M1 table after each CPI release peaked at 5.7% in the three quarters from December 2022 to June 2023. Two quarters before the start of this 5.7% run the measure was up 5.1%. Two quarters after at the end of last year it was up 4.5%.

Despite the legitimate worry one can have about inflation from business pricing expectations getting stuck at twice their long-term average, core measures seemingly favoured by the Reserve Bank are tending to fall faster than the shock speed at which they shot up.

If I were running the show on The Terrace, I would definitely not feel inclined to do borrowers a favour at the moment and either signal to banks that they can cut their fixed lending rates or signal generally that I was happy with the inflation outlook. But I also would not feel inclined to raise the cash rate again because of the risk that this would be an over-tightening for which the eventual response would have to be very rapidly cutting rates from late this year.

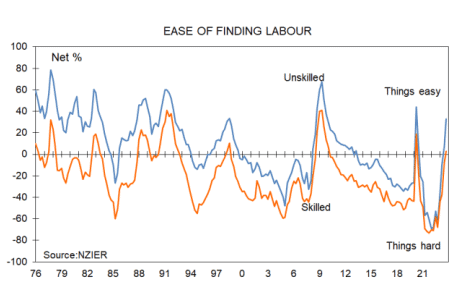

There is another thing to consider regarding the change in monetary policy view in response to last week’s employment data. The Household Labour Force Survey has an established record of throwing up occasional rogue results and there is a strong risk that has happened for the December quarter.

The NZIER’s Quarterly Survey of Opinion for the quarter has shown businesses feel the availability of labour is the best it has been in 14 years.

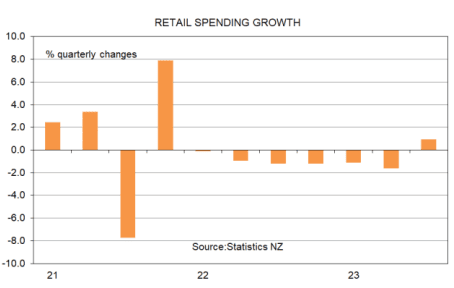

Of significance also is the fact that the labour market lags changes in the economy’s growth rate. The key route by which the Reserve Bank wants higher interest rates to work – crunched consumer spending – is functioning perfectly. Retail spending volumes have declined in six of the last seven quarters and consumer sentiment remains well below average levels.

It pays also to note that there is extra restraint on the economy yet to be felt as people keep rolling onto higher fixed mortgage rates. It takes a while for monetary policy changes to affect inflation in New Zealand because of our high use of fixed interest rates. That accentuates the risk that a central bank eases too much on the way down as they grow frustrated waiting for inflation to lift, and tightens too much on the way up as they grow frustrated waiting for inflation to fall.

Having said that none of us should expect monetary policy changes over any cycle to be optimal. There will be tightening that is too slow or too fast, loosening that is too slow or too fast, steadiness in rates that is too extended. Borrowers need to recognise that the Reserve Bank is engaging in as much guesswork about where the economy and inflation are headed as the rest of us and factor this into their interest rate risk hedging decisions. I’m of the view that there will be some catch-up rate easing down the track which will get borrowers quite excited and spark new life into the rising housing market. But we’re not there yet. The first signal from the Reserve Bank that they are feeling more relaxed may be behind the doors indications to banks that the RB would not get upset if they were to pass lower wholesale borrowing costs into lower fixed mortgage rates. Maybe that will come in the June quarter. But who knows what we will learn about NZ and global inflation pressures by then, let alone by the end of 2025?

Article published 15 February 2024

By Tony Alexander, Economist

https://www.tonyalexander.nz/